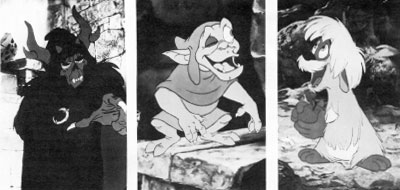

Not too surprisingly, the evil characters are far more interesting than the good ones, and the nasties in The Black Cauldron are the most gruesome to appear in any Disney movie since Fantasia. Especially grotesque is the cauldron-born army of skeletal warriors which come to life dripping rather more slime and gore than one normally finds in a ‘U’ certificate film. The Horned King himself is a particularly unpleasant piece of work, although he lacks the dignity and calculating malice of either the Queen in Snow White or Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty, and only possesses a fraction of the elemental pagan power which Disney’s animators bestowed on the demon of Bald Mountain in Fantasia. Attending the Horned King is a character who is unquestionably the real star of the movie: a diminutive, bug-eyed lizard-man named Creeper whose ineptitude and total unsuitability for his job constantly incurs the wrath of his master – and brings some much needed relief to the horrific goings on.

Many of The Black Cauldron’s problems have been caused, or at least compounded, by the variable quality of the animation itself. This is no doubt a reflection of the film’s lengthy production schedule and the fact that so many diverse hands have worked on it. There are visible differences between the appearance of characters from one sequence to another, and quite inexplicably Gurgi is drawn with grey-green ink on his first appearance and thereafter outlined in black like everyone else.

This is the first Disney movie in the post-Xerox era where the process looks like the economy which it is. What worked so effectively in films like 101 Dalmatians and The Sword in the Stone, where characters and backgrounds were equally stylised, does not work here. Taran and Eilonwy move through the ornately Gothic setting of the Horned King’s castle like cartoon-strip characters wandering across an oil painting by Bosch. And silhouetted against live-action skies they look as disembodied as real actors do when performing in front of a blue-screen.

The film’s impressive cast of voices is headed by Freddie Jones and Nigel Hawthorne with John Houston as Narrator and John Hurt at his most vocally menacing as the Horned King. Grant Bardsley and Susan Sheridan speak nicely enough for the young hero and heroine, but have precious little to work with in the way of convincing dialogue. Elmer Bernstein’s score (with a different musical motif for each of the characters) is imaginative and exciting, although infinitely more so for the sequences of terror and suspense than for those of hobbity pastorale.

What distinguishes The Black Cauldron as a remarkable film, despite all its shortcomings, is its stunning use of special effects: fires, explosions, visions, enchantments and transformations which use the film’s 70mm format with great success. Many of these sequences have been achieved through the use of video, computer-graphics and other technological innovations (a discussion of which can be found in the July 1985 issue of American Cinematographer). Nevertheless, quite run-of-the-mill effects, such as the opening multiplane-shot moving through the trees towards the pig-keeper’s cottage, are unbelievably crude and shaky; and the use of live-action footage to create the smoking cauldron is a terrible cheat since the prime purpose of animation is surely to achieve those things which the ordinary film-maker cannot.

Among the best use of effects are the scene in which Taran first encounters the forces of evil: the diving, wheeling griffins (scaled-down versions of the black-and-purple dragon in Sleeping Beauty pursuing Hen Wen across a moving landscape; and the final shudderingly frightful disintegration of the Horned King as he is sucked into the Cauldron (although even the youngest movie-critic will find this rather reminiscent of the melting Germans in the conclusion to Raiders of the Lost Ark).

But effects do not a movie make, and are certainly no substitute for good characters and a strong storyline. The failings in the plot are too legion to be catalogued here; but, by way of example, it is totally absurd that the silly witches who have no power over the Cauldron in Reel Two should be able to reverse its magic and conveniently bring Gurgi back to life at the end of Reel Three.

Roy E. Disney, Walt’s nephew who recently returned to the studio to oversee animated film production, has expressed his belief that the Disney Studio is ‘getting to the point where the staff is the best in the Studio’s history.’ Only time will tell. As for the The Black Cauldron, it remains a largely disappointing experience: some undoubtedly amazing pyrotechnics, undermined by some incredible misjudgements.

That said, the film will, in all likelihood, do excellent business. In an age when, as the newly-appointed Studio bosses have said, the Disney organization ‘cannot rely on the Disney name and reputation alone to satisfy the entertainment tastes of a new generation’, that is probably all that counts.

All illustrations in this article copyright © MCMLXXXV Walt Disney Productions.

page 1 | page 2

Printed in Animator Issue 15 (Spring 1986)